Filmer av Stefan Jarl

S-tänk

Snutarna

Dom kallar oss mods

Bekämpa byråkratin

Gisslan berättar

Förvandla Sverige

Bojkott

Vi har vår egen sång-musikfilmen

Ett anständigt liv

Memento mori

Naturens hämnd

En av oss

Själen är större än världen

Hotet/Uhkkadus

Tiden har inget namn

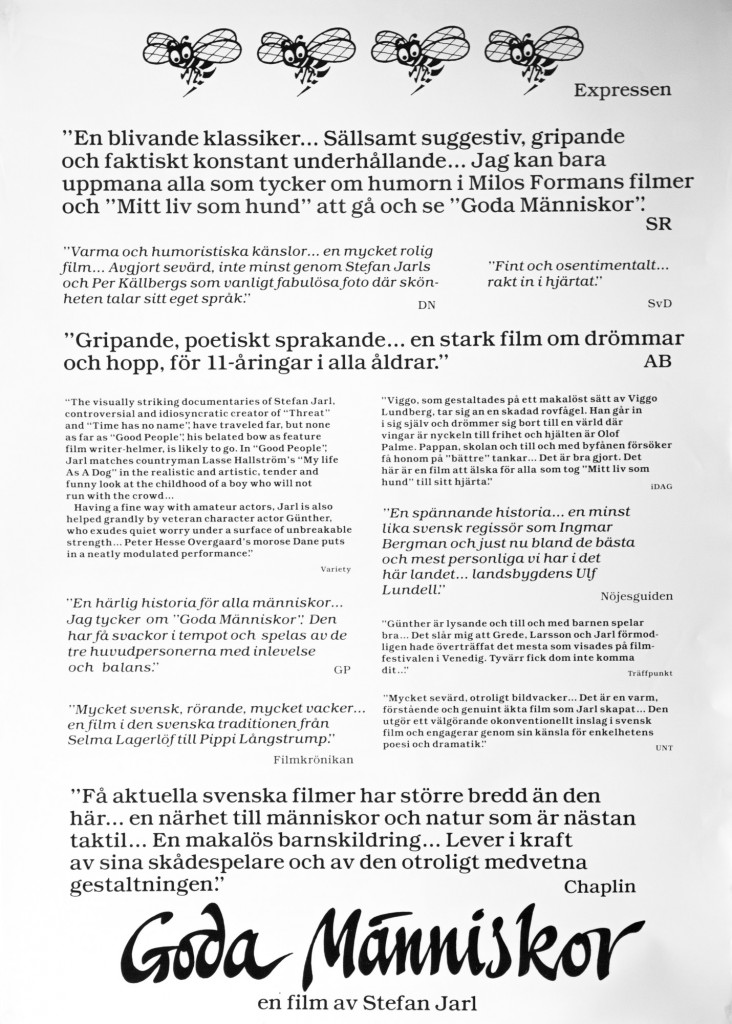

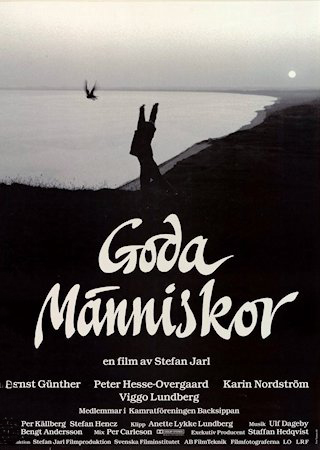

Goda människor

Jåvna, renskötare år 2000

Det sociala arvet

Samernas land/Same Ätnam

Jag är din krigare

Liv till varje pris

De hemlösa

The Jan Troell Band

Skönheten skall rädda världen

Gästgivargår´n

Hårdare tag

Muraren

Terrorister – en film om dom dömda

Paradise lost

Flickan från Auschwitz

Epilog

Kor är fina

Min kompis kajan

Om kajors intelligens

Underkastelsen

Underkastelsen – En bakomfilm

Godheten

Koltrasten

State of Mind

Ojämlikhet dödar

Ett barn är fött

Homo Narrans

All that is solid melts into air

5 år efter Underkastelsen

Innan vintern kommer

Brevfilmen

Själen för fan – kortfilmen

Rannsakan

Själen för fan – långfilmen